There’s hardly a topic right now that causes greater uncertainty and produces more misinformation in the field of nutrition than sugar substitutes – and artificial sweeteners in particular. Almost every day, one stumbles upon headlines in blog posts and newspaper articles which would like to educate us about some shocking truths.

Starting with such sweeping statement that ’artificial sweeteners are harmful to health’ right up to allegations such as ’sweeteners make you fat and are used in hog feeding’, ’sweeteners cause diabetes’ or even ’sweeteners are carcinogenic’.

Health-conscious readers will shake their heads – horrified – and dump their sweetener packages straight into the bin.

In many cases, the author does not even bother to mention what kind of artificial sweetener he or she is dragging through the mud. Because: every type is equally bad, isn’t it?

But let’s start from scratch. There are three reasons that led to the unbelievably bad reputation of artificial sweeteners.

- bad studies

- the dynamics that bad news spread around the web incredibly quickly and stay around much more tenaciously than good news (’I read somewhere that …’)

- the fact that authors have little knowledge or not even the faintest idea of the matter, so they simply quote other authors (as to say, ‘copy’ from them) without themselves checking the sources mentioned

A bad study is a study presenting a result that is in no way linked to the facts or that establishes a cause and effect relationship when it is not, and here, surveys come out on top: you invite a group of people and question them about their eating habits. Besides the fact that the validity of such a survey is questionable, the conclusions drawn from the survey results are largely dependent upon which outcome is desired.

Another example of a bad study is the collection of bare facts between which there appears to be a causal relationship, but only because it’s wrongly interpreted.

Example: At a specified period of time, data is collected about what group of people consumes sweeteners very frequently. Soon you’ll discover (quite surprisingly) that diabetics and people who are overweight use sweeteners more often. And those who can count one and one together conclude that it is exactly this group of people that tries to avoid sugar and uses sweeteners instead. Sounds logical, doesn’t it?

However, the correlation can also be interpreted inversely presenting the following result: sweeteners increase the risk of overweight and diabetes. Soon after, this appears as a headline in a local rag without further explaining the circumstances of such a study. Do you see the problem?

Do artificial sweeteners cause diabetes and obesity?

A frequently quoted study for example is this one [1]

:

In this study, more than 66,000 women were observed over a period of 14 years and examined later on whether they developed type 2 diabetes.

Then they tried, on the basis of the data, to establish a relationship between the consumption of beverages sweetened with different sweeteners (sugar, artificial sweeteners and unsweetened fruit juices) and the incidence of type 2 diabetes. To get a meaningful statement, all women would need to get a nutrition with the same nutritional composition (fat, protein, carbs) and only ADDITIONALLY, a specified quantity of three different beverages.

Of course, this was not the case –how could they manage, with 66,000 women over a period of 14 years? They were allowed to eat and drink whatever they liked and were just told to document their eating habits.

They simply recorded how much of each type of beverage had been consumed. Although the study report says that total energy intake and macronutrient distribution, health history and other facts relating to lifestyle (education, alcohol consumption, genetic predisposition and some more) were documented, too, however, the respective data will not be disclosed.

Apparently, it did not matter at all if the participants consumed any of the three beverage types. As a consequence, these showed up in all three categories of the statistic.

Finally, they concluded that type 2 diabetes occured more frequently in those participants who consumed very large amounts of sugary beverages and drinks sweetened with artificial sweeteners, whereas there was no correlation found when consuming large quantities of fruit juice.

What does this tell us? Absolutely nothing!

Let’s just take two fictive persons, participant X and participant Y, both female.

Participant X is relatively slim, does a lot of sport and is as sound as a bell. She has a glass of fruit juice for breakfast, a glass of sugary lemonade for lunch and favorites a more or less low-carb diet with a daily intake of less than 100g carbs.

Participant Y is overweight, lives mainly on a high-carb diet and exclusively drinks (as she is almost always on a diet) diet coke.

Sixty-four-dollar question: which of the two is more likely to get type 2 diabetes? Anybody who has just grasped a little of all the interrelationships between the consumption of carbohydrates and the incidence of insulin resistance, obesity and type 2 diabetes, will be able to answer this question very clearly. The study with its millions of datasets sorts participant X into the category ’sugary beverages’ and ’fruit juices’, whereas participant Y is only put into the category ‘beverages sweetened with artificial sweeteners’.

While Y underpins the evidence that sweeteners contribute to an increase in diabetes, X influences the results so that sugary beverages don’t lead to an increase in diabetes and neither does the consumption of fruit juices.

But stop…. Hasn’t the study just found that also sugary beverages cause diabetes? But that’s obviously not the case with fruit juices. I SEE!

Is anybody else just getting so confused??

The game could be continued almost endlessly – this will not make empirical evidence of this study any more meaningful.

Fact is (and that’s absolutely scientifically proven): the incidence of type 2 diabetes is directly linked to (causal) a high intake of carbohydrates. Therefore it is also commonly known as ‘sugar illness’. It doesn’t matter in the slightest if you still add 2 liters of diet coke to your daily 250g-carb intake. But additionally consuming 2 liters of sugary coke would surely speed up the process.

It is also a fact that (and if you look around your circle of acquaintances, you’ll confirm this) people with overweight and/or diabetes would rather go for sugar-free alternatives. After all, they want to see their bodies undergo a noticeable change. Just skipping sugary drinks from your diet is simply not enough if you continue to eat pasta, grain and sugar, but that is another story.

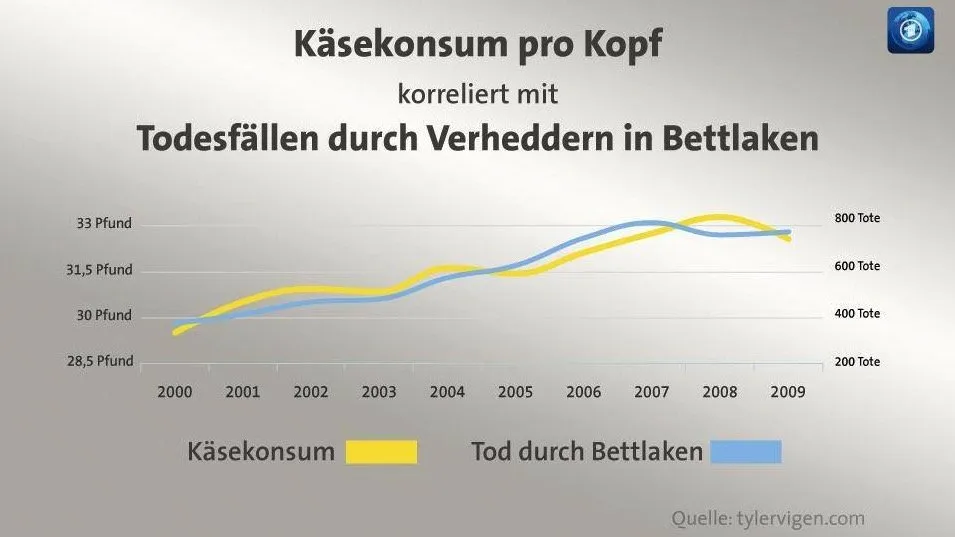

Statistics in general need to be taken with a grain of salt. Another example for a so-called ’idiotic statistic’ is the very popular correlation between consuming cheese products and deaths caused by getting tangled in bedsheets. Ever heard of it?

Another frequently quoted study is this one [2]

Here, they claim to have found out that there exists a link between obesity and the consumption of sweeteners.

This is also a classic survey study where the test persons simply have to fill in questionnaires on their eating habits. Diet diaries had to be kept by every participant on 7 days of the week and recorded in very irregular intervals over a period of unbelievable 28 years, finally, extrapolated for the entire duration of the study. That alone is an impressive waste of research funds, if you ask me, but anyway…

What stands out is that (if you read the study completely) the test persons who consume sweeteners in general were already fatter before the study started than those who don’t. And that’s no surprise since overweight people would rather resort to sweetening agents in order to change that. And in fact, there really is a causal relationship, but it is precisely the opposite of what ‘scientists’ would like to establish.

The result of this study: the group of people consuming sweeteners was just as fat or even fatter than before. Does this really tell us that sweeteners are to blame for that?

That may very well be – unless you’ll have a closer look at the chart on page 6. There, it states that ALL test persons were on a high-carb diet, containing a daily intake between 230 – 245g (!!!).

What does this tell us? That sweeteners won’t do the job if you don’t switch to a low carb diet in general. That means, just drinking diet coke cannot ‘erase’ amounts of burgers and fries.

Somehow that is logical, isn’t it?

Do sweeteners harm your gut bacteria?

Wherever you turn when discussing the effects of sweetening agents on intestinal flora, this Nature Paper repeatedly turns up [3]:.

Let’s have a closer look at that:

(SPOILER ALERT: this is also a crap study)

If you would like to get a deeper insight:

The study found a link between changes in gut bacteria (increase of glucose intolerance) in MICE when consuming three (!!!) different types of sweeteners. These 3 sweeteners could hardly be more different, they have a completely different chemical structure. That is a little bit like doing a study with potatoes, tomato juice and cottage cheese and getting a quite similar result with all three of them – but would lead to a significantly different result when taking apples instead. As a logical thinking person one might be lead to think that the apples (called ‘sugar’ in the study) are the ones that step out of the line. That’s only logical, after all, it has been a known fact for a long time that sugar withdrawal will lead to a change in your gut flora – this is called physiological insulin resistance and is perfectly normal. Instead, the results are interpreted exactly the other way round: of course, the sweeteners are to blame for that.

Apart from the highly questionable test result from experiments on mice, they further evaluated a survey made on people (small surprise) and showed that those who consume more sweetening agents tend to be fatter and suffer more frequently from diabetes – really no surprise, thin people surely are not too concerned about whether they should drink standard coke or rather diet coke (we have already discussed this one…).

In addition, they carried out a brief study giving all test persons (just 7) the maximum daily dose of saccharin. After one week, 4 out of the 7 test persons showed a lower level of glucose tolerance, the remaining 3 showed no signs of change.

What does that mean? NOTHING AT ALL, the authors leave us in the dark about what kind of food these people consumed beyond that (in addition to the sweetener): Were they forced to exactly maintain their eating habits? Did they consume the sweetener in the form of lemonade and drank less sugary lemonade as a consequence? Did they sweeten their entire food with it or were they allowed to eat as much of it as they wanted?

We know nothing at all. But anyone who looks at the experimental part of the study will recognize that those test persons who showed ’no changes’ according to the authors, showed a slightly higher level of glucose tolerance. Funny, isn’t it?

7 people, 4 of them showed worse values, 3 of them better ones, really awesome! And all that after only one week. In the field of chemistry, one would classify the experiment as ’no result, not enough data’. In medicine, there’s obviously not much point in worrying about published data that do not make any sense from a scientific point of view. As long as the headline sounds impressive and the article can be published in the Nature Journal…

The bad aspartame

Aspartame takes the cake when it comes to unpopularity and horror stories. You really don’t know where to start. So let’s have a closer look at one of the latest studies [4]:

Does aspartame hinder weight loss efforts?

In this study conducted in 2016, a research team identified the degradation product phenylalanine (aspartame is metabolized in the body to phenylalanine, aspartic acid and methanol) as being the bad guy. It is alleged to have negative effects on a specific enzyme which prevents progression of the metabolic syndrome. Only by looking closer at the study, you will encounter some curious facts:

The quantity of phenylalanine contained in 5 liters of diet coke corresponds approximately to the same amount of phenylalanine as in 200g chicken breast. So does that really mean that chicken breast makes you fat?

Phenylalanine is an essential amino acid and, by the way, is also sold as dietary supplement to INDUCE an effective weight loss: as it also promotes an increased release of dopamine, you are full of energy and can work at full throttle in the muscles factory and, on the whole, it will help you to feel less hungry.

Well… the authors should better have looked up the term ‘phenylalanine’ in Wikipedia and learned what it’s all about …. No wonder, the Science Daily is more of a local rag in the science world, just like the German BILD Zeitung. If you can really call it science, though.

Aspartame: toxic methanol, cancer and so on

In this context, we don’t need to write that much. There are already (fortunately!) some summaries around in this respect, which are absolutely recommendable and there’s nothing left to be added:

Short and sweet at Dr. Strunz:

Aspartame and cancer – Enough is enough (German)

Two bananas (about the bad degradation products of aspartame – quite amusing! in German)

or, explained in a very detailed manner at Aesir Sports:

To conclude, just a few words

There is a good deal of very emotional discussions about ’good’ and ’bad’ sweeteners where scientific evidence can so easily be ignored. Statements such as ’I’ve recently read somewhere that … ‘ or ‘as everyone knows, … ’ really do contribute to further fuelling this myth instead of providing correct information. Even if you put all studies to the acid test that claim to have found evidence of negative health effects of a certain sweetening agent and present a significantly more valid study instead which is able to prove exactly the contrary, you’d certainly end up with the killer phrase ‘Hey, this positive study is surely industry-sponsored, I don’t believe this stuff’. And even though this phrase, at first sight, may be quite plausible for conspiracists – the questions about how this would be funded in connection with credibility cannot be answered on this basis. (If you want to look closer, we recommend you to read this article in Aesir Sports: Is there a big aspartame conspiracy? German))

We had worked our way through hundreds of studies. This summary explains just a small part of it – otherwise this would be a bulky volume and not a clear and concise blog article. We will discuss some more myths fully later in separate articles. In addition, we continue to stay up-to-date on recent research activities in this field. At present, there’s no need for us to worry about using selected sweetening agents in our products (please read our article on this topic). And, by the way: we at Dr. Almond eat them, too …

Have you come across a study about sweeteners that causes you headaches? Just use our comment function and link it – we would be happy to have a look at it and evaluate the study correctly.

[1]http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/97/3/517.long

[2]http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0167241&type=printable

[3]https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/pdf/nature13793.pdf

[4]https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/11/161122193100.htm